Lord William Howard (1563 -1640), known as ‘Belted Will’, was the son of the Duke of Norfolk, whose marriage in 1563 to the widow of Thomas, Lord Dacre of Gilsland, had promised that he would inherit the Dacre lands. Norfolk’s Catholic allegiance led to his being beheaded for his support of Mary Queen of Scots, but he had previously committed his three sons to marry the three daughters of Lord Dacre’s widow by her previous marriage. ‘Belted Will’ married his choice of the Dacre daughters – Elisabeth – in 1577, wishing to enter the Gilsland part of the Dacre inheritance. But the couple’s access to the estate was long deferred. Following the Dacres’ uprising and defeat at High Gelt Bridge in 1570, their estates were attained to Queen Elizabeth who sustained control during her lifetime.

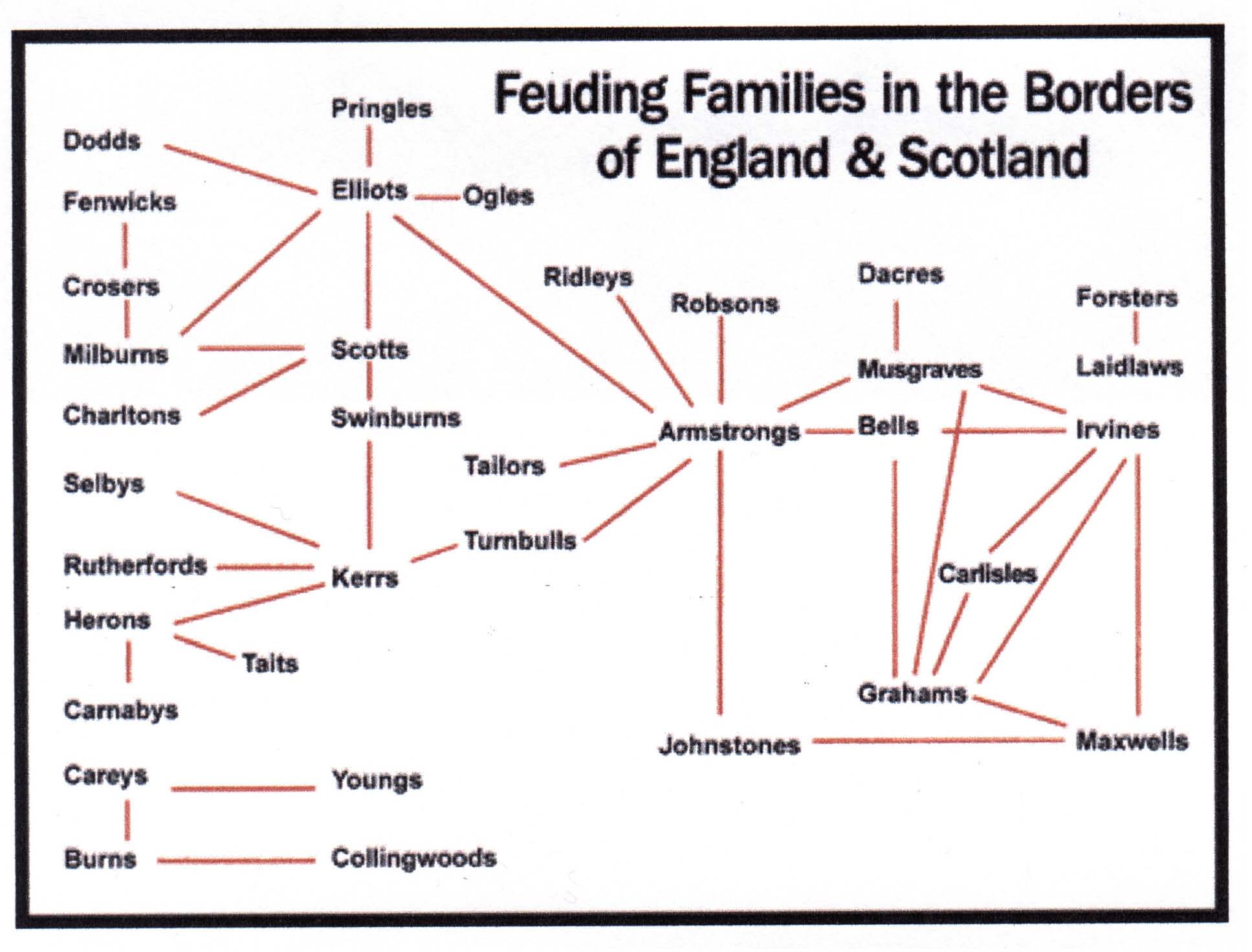

The Barony of Gilsland contained 20 manors from Farlam in the east to Irthington in the west. Each manor was overseen by a bailiff under the command of the land serjeant of Gilsland, a role held towards the end of the 16th. Century by Thomas Carleton in succession to his father. The Carletons were rogues and as dubious as the Musgraves, who for centuries had sustained a vendetta with the Dacres. The Carletons had colluded with the Scots in atrocities amongst the tenants of Gilsland, the majority of whom held tenant right. Carleton’s behaviour made him a thorn in the side of Scrope, his nominal superior as Warden of the Western Marches. In 1598, however, Carleton was killed in the unusual course for him of pursuing English miscreants. His similarly disreputable brother Lance – who was bailiff at Brampton – hoped to succeed his brother as land-serjeant of Gilsland, but the post was given to John Musgrave, who had held the grant of Askerton Castle. In league with the Grahams of Esk, the Carletons had previously tried to murder Musgrave at Brampton. The Carleton feud with the Musgraves was sustained when in 1602 a duel between John Musgrave and Lance Carleton – which both men survived — was arranged at Canonbie in the Debateable Lands.

Upon Elizabeth’s death in 1603 there was immediate further marauding and damage by Scots and the Grahams, but a main effort of pacification of the Borders occurred in the first four years following James’s accession in 1606. There was disarming of the Marches, displacement of the Warden system and forced evacuation of riding families – particularly the Grahams. The Border Commission of 5 Scots and 5 English appointed in 1605 ensured a new order by barbarous suppression of past miscreants.

Deprived for 25 years of the estate which Howard had wished his marriage to gain for him, only in 1601 and by payment of a fine of £10,000 did he prise Gilsland from the Queen’s hands. Howard’s access to the former Dacre lands and the Barony came after a hard period in the 1590’s of harvest failure, followed in 1597 by a terrible plague in Gilsland and Carlisle. Heavy deaths, famine and stealing by the clansmen of Bewcastle and Gilsland exacerbated the area’s decline. Scrope, the Warden of the West March, had numerous stewards, bailiffs and keepers of castles in the baronies of Burgh and Gilsland, but they operated largely free of control which Scrope weakly exercised. Thomas Musgrave, constable of Bewcastle and his bailiff at Crookburn were amongst the most notorious reivers. They continued to support the Graemes even after 1603, when Bewcastle became isolated in its criminality while Gilsland and Nicholforest came under firm control.

Deprived for 25 years of the estate which Howard had wished his marriage to gain for him, only in 1601 and by payment of a fine of £10,000 did he prise Gilsland from the Queen’s hands. Howard’s access to the former Dacre lands and the Barony came after a hard period in the 1590’s of harvest failure, followed in 1597 by a terrible plague in Gilsland and Carlisle. Heavy deaths, famine and stealing by the clansmen of Bewcastle and Gilsland exacerbated the area’s decline. Scrope, the Warden of the West March, had numerous stewards, bailiffs and keepers of castles in the baronies of Burgh and Gilsland, but they operated largely free of control which Scrope weakly exercised. Thomas Musgrave, constable of Bewcastle and his bailiff at Crookburn were amongst the most notorious reivers. They continued to support the Graemes even after 1603, when Bewcastle became isolated in its criminality while Gilsland and Nicholforest came under firm control.

As Border turbulence generally faded after 1603, it became safer to hold land and there were rich pickings for new gentry by dispossession of previous holdings. However, Howard’s entry to the estate of Gilsland was unwelcome to many in Cumberland, and to counter the loyalty of the Gilsland tenantry to the Dacres he established a small following outside the main gentry groupings, undertaking a survey of the manors of his lands in 1603 and establishing the family seat at Naworth Castle in 1607.

It was in this period of stabilisation after ‘Belted Will’ Howard’s return that the Wannops appear to have gained prominence. In 1592 when Thomas Carleton was the Gilsland Land Serjeant, Ambrose Carleton, gentleman, was Bayliff of Crosbie. Christopher Blennerhasset was bailiff of the Irthington Manor in 1597, and while the barony remained attained by the Crown he was responsible to Thomas Carleton. However, when Thomas died the Carleton family was displaced by the succession of John Musgrave. In 1601, the Carlisle City Court Books first refer to debts to John Wannop, yeoman of Newby. It may be that he became bailliff in that year. There are numerous references to him in subsequent years.

John Wannop must have had an important part in Howard’s drive to protect his tenantry and realise the full potential of income from the estate. Appointment as bailiff may have soon followed Howard’s full assumption of the Naworth estate, although only from 1612 is John formally recorded in the Naworth Household Books as ‘bayly at Nuby’. Thereafter, up to 1652, at least, many records show him as‘ bayliffe at Irdington Manor’ and at ‘Newbie, Crosbie and Weobie’. In 1645 the records refer to John Wannop, senior, of Newby, so it could be that a father and son named John were successively bailliff. It is also possible – but not certain – that the John Wannop of Newby who was churchwarden at Irthington in 1674 was the same as he who had been bailiff in 1612.

With restoration of the fortunes of the Howard family and of Gilsland, Naworth Castle itself was repaired between 1605 and 1620. While the Borders remained disturbed, a garrison of some 140 armed men was maintained at the Castle. Howard’s continuing attachment to Catholicism is disputed, but by 1618 he had become sufficiently acceptable to assume the role of Warden of the Western Marches.

‘Tenant right’ prior to 1600 had allowed relatively favourable rents in return for an obligation to bear arms in defence (or attack) against the Scots and the reivers. After his accession, the new King James pressed Lord William Howard to abolish tenant right and to substitute leases at higher rents. The King wished to reduce the likelihood that the Gilsland men would pursue James’s subjects in or from Scotland. There was financial advantage to Howard in choosing to cooperate, which he did, demanding in October 1610 that his customary tenants sign a petition to him to abolish tenant right and to receive new leases to their tenements at enhanced rents.

The Gilsland people wished to retain tenant-right, which the majority held and which was of increasing advantage to them as Border wars faded away. The people were famously independent, having had only a light rein on them during the long period of the 16th Century when the Gilsland estate was attained to the Crown. They were a turbulent tenantry, and in spring 1611 some 200 assembled at High Gelt Bridge to protest. Thomas Salkeld and John Dacre, the ring leaders, were subsequently imprisoned in the Fleet prison and fined. But ten years later, the long-standing dispute between Howard and the Gilsland tenants ended when – after reference to the Star Chamber – it was declared that there had not been a formal obligation to bear arms under tenant right, but merely a civic expectation falling upon anyone, high or low. So the ancient customary tenure was revived and harmony restored.

Unfortunately, because still in the Crown’s charge, the Irthington Manor was excluded from the Gilsland Survey of 1603. No Wannop is recorded in the other 14 manors of Gilsland, so it is very possible that all of the name were contained in Irthington at that period. Other names in the Survey of the Manor of Hayton would marry into Wannop lines, however i.e:

‘Manor of Hayton – Certain grounds called the Homes on far side of the river Irdinge near Bisshopsforde; by said river on the east, south and west, etc. Various furlongs and pieces – Tho. Railton, Jo. Railton, James Railton, Jo. Gill, Jenkin Dalton, Tho. Graham, etc.’

John Waynop’s emergence as bailiff at Newby in the Irthington manor coincided with Howard’s effort to replace tenant-right on the Naworth estate by leasehold and raised rents, in a period when reiving was disappearing and unprecedented order was being brought to the Borders. The great extent of common land was a remarkable feature of Gilsland. 1,762 acres out of 5,550 in Brampton were common, 68% in Hayton and Castle Carrock together and 44% in Gilsland as a whole, excluding Irthington.

Following his visit to Gilsland in 1599, William Camden’s Britannia described local transhumance: ‘Every way round about in the wasts….you may see it as it were the ancient Nomades, a martiall kind of men, who from the moneth of Aprill unto August, lye about scattering and summering (as they tearme it) with their cattell in little cottages here and there which they call Sheales and Shealings.’ There were sheiling grounds at Bewcastle and on Askerton North Moor, which until the mid 1600’s was still used for summer grazing by tenants of seven of the Gilsland manors.

Although there was some fertile soil in Hayton, Walton, Irthington, Brampton and Nether Denton, the main concern of the tenantry was pastoral rather than agricultural. Open fields reached their maximum extent about 1600, although probably less than 50% in the Walton and Corby areas. The rigs were not periodically allocated but cultivated individually. In Hayton, rigs were sown in grain for year after year, without fallow spells. Unenclosed commons and wastes were grazed pasture. Tenants of open fields and enclosed holdings were often blood relations; an instance was in Talkin where there 13 tenants were named Milburne.

There were four types of tenure on the Howard estates:

- Leasehold. This tenure was not feudal in origin but emerged in the 1600’s on former demesne farms or farms enclosed from former waste and common land.

- Free tenants. A small group of manorial tenants held what were known as ‘free tenements’. The original occupiers would have been freemen and not serfs. By the post-medieval period, these tenants had become almost freeholders, owing only a small annual rent and not obligatory services as owed by customary tenants.

- Customary tenants. These comprised the majority of manorial tenants, holding customary tenements (or copyholds). Customary tenants could behave almost as freeholders, being able to buy, sell, mortgage or inherit their lands without interference by the Lord provided they kept to the manor’s customs. Copyholders had to pay a low customary rent, perform various tasks for the Lord (later commuted to money payments) and pay fines on the death of the Lord or at entry of a new tenant or the sale of the tenement.

- Cottagers were customary tenants occupying less than four acres of land.

John Waynop’s services as ‘baillif at Nuby’ to Lord William Howard of Naworth Castle presaged four centuries in which Wannops were prominent yeomen, significant in Cumbrian farming and extensively so around the Irthing and Eden valleys.